As of April 1st, recreational marijuana use became legal in New York, though, that’s not the kind of bud I’m going to be writing about. Earth Day events kicked off this 4/20, and the many environmental actions and summits in the news lately have been filling my feeds and headspace. Though I’m not a pothead, as a college student I wore hemp accessories more frequently than shoes; I’ve definitely held up a hand-painted sign at some point that read, “EVERY DAY IS EARTH DAY;” and I’ve even joined petitions to bestow legal personhood to bodies of water and forests. As a bonafide tree-hugger, the annual budburst brings me a lot of joy.

Spring unfolded early and fast in New York this year. Just a few weeks ago the branches of the basswood in front of my apartment appeared lifeless and dry, and today they’re fully sleeved in tender green spades, jiggling excitedly in the breeze. A giant magnolia tree in the backyard has been waving tightly clenched fist-sized buds at me since late February. Then a run of consistently warm April days transformed it into a frothy plume of cotton candy pink blossoms, seemingly overnight. By the time I took a good look around, nearly all the trees and shrubs in my neighborhood had initiated their unique takes on growth.

The function of buds

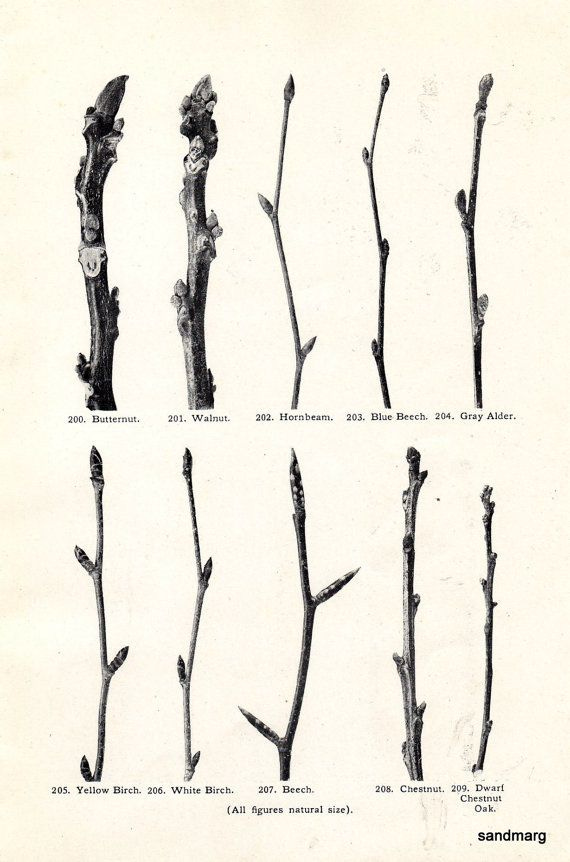

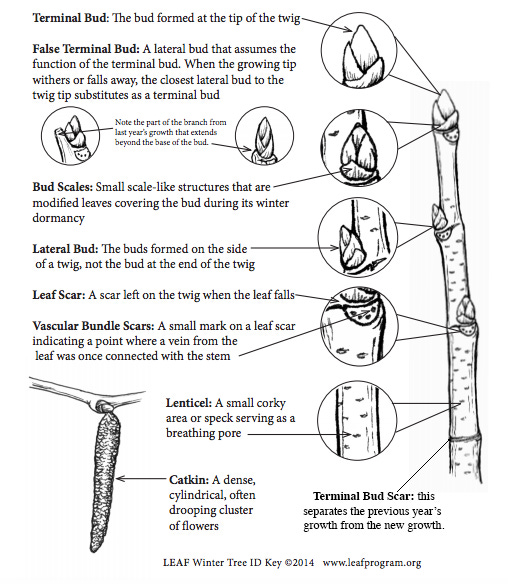

Buds are formed during the growing season and contain the next year’s flowers, leaves, and stems in their embryonic state. They are typically sealed by shell-like bud scales that protect them throughout winter dormancy. How trees “know” when to break that dormancy and open their buds is a question people have been puzzling over for a long time. In recent years, scientists have confirmed that trees utilize a complex system of environmental feedback and chemistry when making that determination.

Trees have light receptors that sense red and blue light plus UVB radiation. Located in leaves, stems, and the tips of roots, they enable the tree to measure day length. When the nights grow longer as the hemisphere tilts away from the sun, the decrease in light detected prompts the tree to produce a hormone called abscisic acid (ABA). ABA inhibits growth, cues the draining of water from leaves and branches, and stimulates the “hardening off” process that makes it possible for the tree’s live tissues to withstand freezing temperatures without splitting open. In deciduous trees, it promotes the growth of cork that closes leaf stems off from the branch, causing them to die and drop off.

ABA also promotes the production of callose, a regulator compound that inhibits bud growth cells. It takes a prolonged period of cold temperatures (44-30 degrees F) to break up this callose compound, and so a number of “chill-hours” must accrue before growth signals can get through again. This is meant to prevent the tree from budding prematurely during unseasonably warm spells in winter. In spring, with sufficient chill hours banked, the channels of communication to the buds open and the tree now tracks how long it has been warm. When the requisite hours of heat and daylight have been met, the tree gets its juices flowing again. ABA is flushed, water swells its tissues once more, and the bud scales open, unfolding the tender origami they’ve been encasing for so long.

Arrangement, grouping, and function of buds varies between plants, as does the order of growth. Some trees start with vegetative growth and use their photosynthesizing leaves to aid in the production of flowers and seeds later on. Others use all of their energy stores from the previous season to produce their flowers first. This makes it easier for insects or the wind to distribute the tree’s pollen before leaves get in the way. Having taken care of their reproductive cycle early on, these trees can then spend the rest of the season focused on growth and fruit development.

Trees and climate change

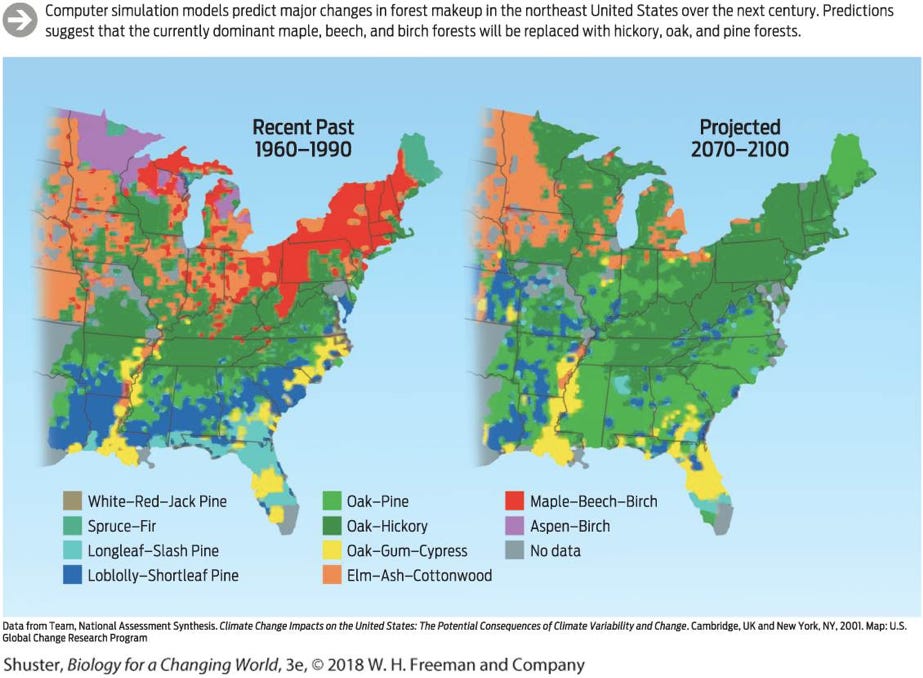

As climate change increases global warming, we’re seeing more erratic weather patterns and record high temperatures in biomes around the world. This year, Japan’s revered cherry blossoms reached their peak in the last week of March, the earliest date since they began formally keeping track in 1953. Some areas experiencing shorter cold seasons and less annual precipitation are seeing a “migration” of heat-sensitive trees whose saplings are germinating better at the northern and western borders of their ranges, causing a steady shift in the forest makeup.

Though trees have a built-in safeguard against premature budding, they can sometimes be tricked by “false springs,” a growing concern in our times. On a walk in the park during an extended warm spell last November, I saw this happening to a young cherry. Though it wasn't blossoming at its max capacity, the warmth had induced plenty of buds to pop open, and when the winter freeze swept through in earnest the next week, they all succumbed to frost. The tree itself survived and when I revisited it recently, it was absolutely coated in blooms. But that second wave of flowering comes at a cost: because it had already drawn from a finite well of energy to produce the first wave of flowers, it will be playing catch up all year, potentially skimping on overall growth and amount of fruit it produces.

The effect of a warming climate on trees ripples throughout the ecosystem. The timing of vegetative growth affects all of the organisms that live under and within the tree canopy. The flow of sap and the availability of nectar and nutrients impact the entire food web, from bugs to wildlife to humans. Flower and fruit setbacks place a toll on agriculture, leading to costly losses for orchards and adding to the strain on honeybees who are succumbing to Colony Collapse Disorder at a disturbing rate. The loss of maple trees would be profound for New Englanders who harvest their syrup and appreciate their brilliant fall foliage.

I don’t like to end on a note of doom and gloom, so I’ll just say this: the world is changing fast, and humans have played a major role in speeding up that change. We all have a role to play going forward as we strive to stop further degradation of our shared environment and mitigate the damage done. If you are re-wilding a barren plot or just planting a tree in your yard, please consider native varieties that have been cultivated locally. This will help stimulate your local economy, cut down on emissions, and likely make for a hardier plant that is well-adapted to the regional climate and favored by local pollinators. I’ll have more on native plants next month after a tour of the Greenbelt Native Plant Center on Staten Island, NY!

“The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is now.”

Sources:

Earth Day 2021

How do trees know when to awake in spring?, Science Norway

Japan's famous cherry blossoms bloom early as climate warms, AP News

False Spring: How Plants React to Unseasonal Warmth, Urban Ecology Center

Trees on the Move , American Forests

Climate change: Impact on honey bee populations and diseases, Yves Le Conte & Maria Navajas